24/08/2023

This is the second talk given to women at Howler Melbourne on 28/06/2023

Finding my voice . First of all thanks to generationwomen.com for giving me this opportunity to tell my story. This is an excerpt from an ongoing memoir titled Art in a Time of Madness.

“ I have been the object of a stalker since 1996 after I accepted a fully-paid Residency overseas. My stalker disparages me in private, uses my full name in public and disseminates personal details so that any crank could get to me. And in 2004, one did.

I became disturbed. I broke down. I did not react, because my stalker is titled, has influence and public support in Australia and overseas. My stalker is entitled, a millionaire.

I assumed a lofty silence for years. I concentrated on invitations to National and International Exhibitions. I created gardens: a moss garden; a fern garden. The garden became my meditative space. I experienced the healing properties of plants by being close to them.

Whereas the garden was escape from my stalker in daytime, at night, I woke up in a cold sweat thinking of extremes of improbability, checking my webpage for lies ; a tampered photograph, new discreditations. I became paranoid. I stopped exhibiting my work. I had panic attacks.

You might think that to call someone who lives overseas a stalker is paranoic exaggeration. After all, that person is not lurking in a dark alley ready to pounce on you. But to my mind, anyone who is obsessed with you, follows your every move,; anyone who regularly connects your name to misleading information through gossip and on social media, with the intention of discrediting you, is a stalker.

A stalker has the mentality of a thief. The stalker steals your mental energy by diverting your attention from the things that matter. Last year one of my works, done in 1981 appeared at auction in Sydney. The title had been changed to read as an obscenity. No amount of begging and pleading to the auctioneers made any difference because ‘the vendor wants it that way’. ‘But you cannot change the title of an artwork. It’s illegal. who is the vendor?’ ‘I’m sorry, we cannot disclose. The vendor is a valued client’. Appeals to Artslaw were of no help.

Helpless and voiceless I turned to Literature: Maya Angelou: ‘you are not voiceless. You have a voice. You just haven’t used it…I thought of the character in Colm Toibin, Nora Webster and found my voice in the shape of the written word. Words, said Connor Cruise O’Brien are the weapons of the disarmed.

I wrote to my stalker. As the menopause is no longer a taboo subject in public discourse, I feel free to tell you that when I accepted the Artists Residency your husband offered, you, the Administrator were a ranting, raging, menopausal disaster on two legs, suspecting every woman within a fifty-mile radius of yourself of scheming to steal your millionaire’ I outlined all the bullying that went on in the privacy of that Residency and how her continued harassment was a cover-up for what occurred there…

I sent copies of my letter to the people who knew what was happening but never defended me. To them I said: Civilization, said James Baldwin is not destroyed by the wicked, but by the spineless.

The very next day, some hideous remarks and lies about me and my work which were on the Residency website for years, were removed.

My voice didn’t rectify the disruptions to my life and my reputation which had been shot for twenty-six years, but it was an incredible feeling of lightness. I felt vindicated. I created a red garden. I planted a red Japanese maple and painted the old garden wall a burnt red-orange, the colour of Eastern spirituality, the colour of Buddhist monks’ robes. I set green plants against the wall, to complement the red, the colour of anger.

When you face a blank wall, don’t bang your head against it. Create.

Art, and in particular, Writing, is galvanised by anger. I hung a small terracotta plaque from Salisbury cathedral against my red wall with the words ‘God, the first garden made’

The greatest gift a woman can have said Maya Angelou is COURAGE. I didn’t have courage. I found courage when I used my voice.

28/04/2023.

On the 23 February last year I was invited by the company generationwomen.com to speak publicly with five other woman each of a different generation from Generation 20 to Generation 70+, on Finding my Joy. It was an experience which came at the same time as I discovered a disparagement of my work and assassination of my character by the Administrator of an Artists Residency I took in Malaysia in 1995-96. It floored me. It reminded me of a time when I was penalised for being an artist at an Artists Residency

At such a low point in my life, still hounded and vilified for twenty-six years by an inadequate person who had little education in the Arts and less imagination, I thought I would not have the strength to talk about joy. But rising to this invitation was the best cure for that terrible experience of seeing my works spoken of in such nasty terms. It brought back memories of the racism, the cruelty and the loneliness; the danger and the physical assault I experienced at the hands of this person during the nine months of that Residency when I was so far from home and so alone.

But I accepted that invitation to speak on Finding my Joy as a woman my age and I breathed again.

Although I have spoken publicly several times at Universities and TAFE Colleges and once at the AGNSW, the subjects were always tied to paintings, prints and mixed media works. Having to speak publicly on a personal subject like finding joy was a new experience. It was nerve-wracking. But I prepared for it seriously. I spoke of a friendship I found when I was a new migrant to Australia. Alone all day with a new baby on the Blue Mountains, no family; no friends, a neighbour appeared on my doorstep one day and asked me how I was. If the sun and the moon and the stars had all shone out at once they could not have matched the light that came into my soul the day she appeared…

The generous applause I received was a surprising adrenaline rush . I was on a high for days.

Utilise the difficulty. If something devasting happens to you, fry talking about the one spark of joy which flashed during suddenly during that time of fear and sadness. That was something I never thought I could do. But I did it. It was the best thing I ever did for myself.

And thank-you to generationwomen.com for that invaluable experience.

Postscript 1

/Postscript 2

In the past few days, I was shocked by blog posts of the Administrator of the Residency I attended several years ago . While these blog posts purported to be in support of my co-artist (deceased) in that Residency, they turned out in the end to be attempts at assassinating my character and invalidating my work. One’s work is the product of one’s mind. Still reeling, I take refuge in the words of one of my favourite Sufi mystic poets Saadi of Shiraz :

‘No one throws a stone at a barren tree.’

I would really love to hear from anyone who wants to write to me about whatever I have said in my blog posts concerning my time at Rimbun Dahan. I would love to hear something positive which will balance my experience there. I must be allowed the self-respect to state my case, and to tell my story honestly, without being abused.

Renee, my co-artist was not a close friend; but she was not an enemy either. She was my student when she was 17. And to me, she was by that time, already a mature artist; everything seemed to have gone downhill from there. I kept two of her drawings for the 30 odd years we were apart and returned them to her when the Residency was over.

During that Residency, Renee’s personal struggles were exacerbated by menopause (Renee was 51) and her deteriorating health. This affected her performance and her confidence. She lost ground and she left the Residency. Unfortunately, the physical and mental state she was struggling with was exploited by others, in support of their own domestic and social conflicts. The Administrator of the Residency used Renee’s vulnerability to prove her point: that Malaysian women don’t get on. Once Renee left the Residency, every request I made to the Administrator for us to meet, to talk; every request for contact with Renee was denied.

In retrospect, I regret the intensity with which I plunged into painting, and if I could go back in time I would try harder to be there for her. But the excitement of painting outbid everything for me. Although the conditions were inadequate, I was, for the first time in my life free to paint non-stop and I did just that. I was the oldest of the three women at the Rimbun Dahan Artists Residency and I should have paid more attention to the problems under my very nose of two women who were going through the most difficult time in women’s lives: the menopause. I went there to paint; and I never considered expending my energy elsewhere than on painting. .The terrible accusations and unexpected behaviours I witnessed, came as a shock, plunging me further into painting.

We can only see the whole at a distance; sometimes we can only assess hurt and the harm done to us in time. It might help if we understood the source of hurtful behaviour, even if there’s nothing we can do about it.

Mimosa Pudica

/

ART IN A TIME OF MADNESSI

Mimosa Pudica: The sensitive plant, which closes up at the touch.

How do I describe the feelings which overcame me at the news of her passing? There is no single word for it. Emptiness? It was an experience which bruised, scarred, scooped out my soul.

Voided.

As time processes the information of her death —which I only received two years after the event— I struggle to prevent that void, now sealed, from re-opening and filling with old hurts and regrets.

In Malaysia, with its superstitions concerning death and the afterlife, anyone who dies or contracts a disease and dies of it, is beatified, regardless of her past crimes. So, what I am about to reveal in these blogs about my time at the Rimbun Dahan Artists Residency in Malaysia which I shared with Renee Kraal, might be unwelcome to Malaysians who would prefer to forget. But it is only in remembering that we can learn lessons and bring meaning to past experience. And a story as racialised and politicised as this one needs to be told. It is twenty-five years since the Residency. That I have only now, picked up the courage to raise my voice and tell my story, testifies to its traumatic nature.

When I chose to apply for the Rimbun Dahan Artists Residency programme in '95/'96 on Renee's invitation, to work with her, I took it up in all sincerity and good faith. It took years before I could make up for the losses I incurred through that choice: personal, in terms of my reputation —those who do wrong are tireless in their efforts to discredit their victims— in Malaysia and here in Australia; financial, in terms of job prospects and the poor sales at the end of the Residency through foul play; and domestic, in terms of the sacrifices I put my Australian family through, and the breakdown I suffered at the end of that Residency.

Renee was a guru. Gurus are street angels. Behind closed doors, they can be dangerous when denied the superior status they believe is their due. She preached healing; wore her spirituality on her sleeve. She was into Chakras, crystals and Bach Flower Therapies —not Art. So, in applying for the Artists Residency, she had simply knocked on the wrong door. As her co-artist, I was the potential for dominance, within her reach; until I chose to be unreachable. My refusal of her efforts to ‘heal’ me, my concentration on studio work, threw her into a tail spin. That was the crux of the ruin of what might have been an artistically and spiritually rewarding nine-month Residency.

An insecure spirituality flounders at the smallest obstacle. In the face of that insecurity in the very person who preached healing and peaceful inner states, I went into a virtual locked-in syndrome. Like the Mimosa pudica, I closed up when the subject of the Residency or Renee was thrown at me, and no amount of bullying by anyone on her behalf —and there was bullying, mental abuse, and on one occasion, physical abuse—could make me talk about what I was experiencing at the time. Traumatic experiences are best kept private, because the slightest nuance of disbelief can be hurtful. There is strength in silence, resilience in endurance.

For the first 5 months of the nine-month Residency —which were stretched to ten, to satisfy Renee— I was alone in fourteen and a half acres of old orchard, beautiful by day but wild and sinister at night; with no means of communication or transport in the event of an emergency, and no one to talk to, or to trust. Because I believed that Artists in Residence have to separate the professional from the personal, I made no complaint about what was happening to me to the Administrator of the Residency who became increasingly hostile. I feared her as much as I feared Renee's friends who were easily roused to anger on her behalf and quick to fight her battles. Whereas I knew that the mental stability of those who are quick to take sides rather than mitigate ill feelings with rationality, was questionable, I still turned things back on myself and examined the image I was projecting which might have caused antagonism. I came to the conclusion that having been away for so long, I was a Malaysian in a foreign country —Malaysia. There had been no time for mutual adjustment. I had accepted to take a trip on this rocky road and I would have to keep going to the end.

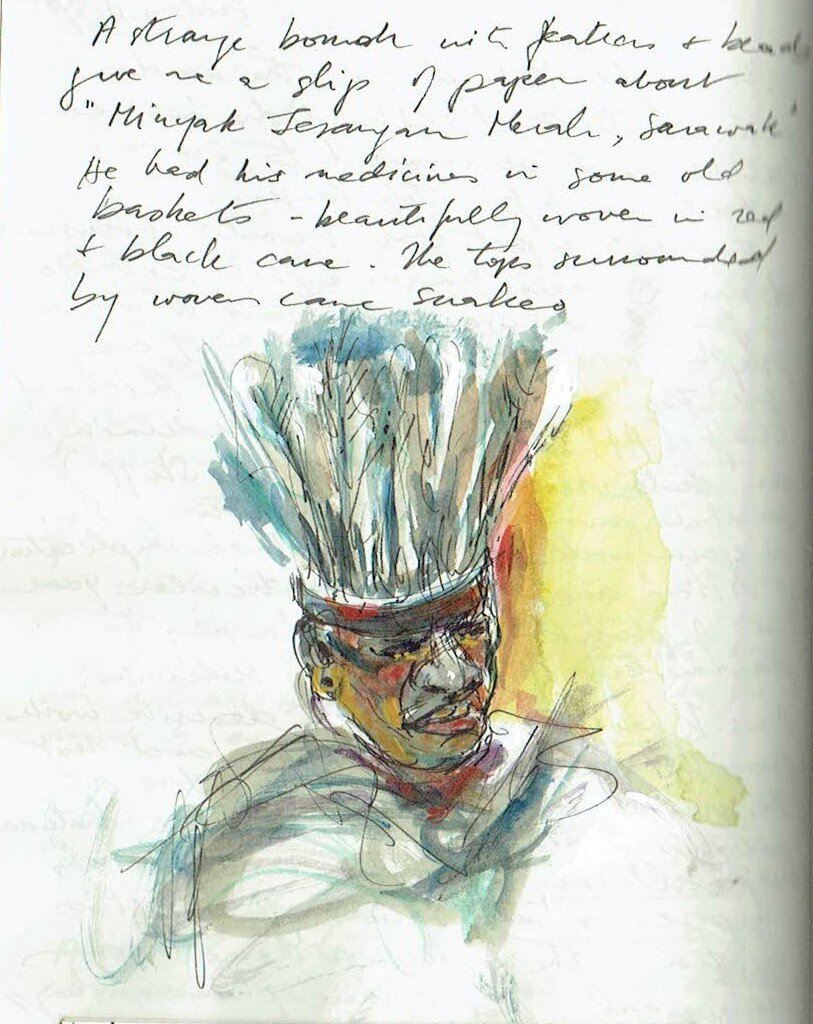

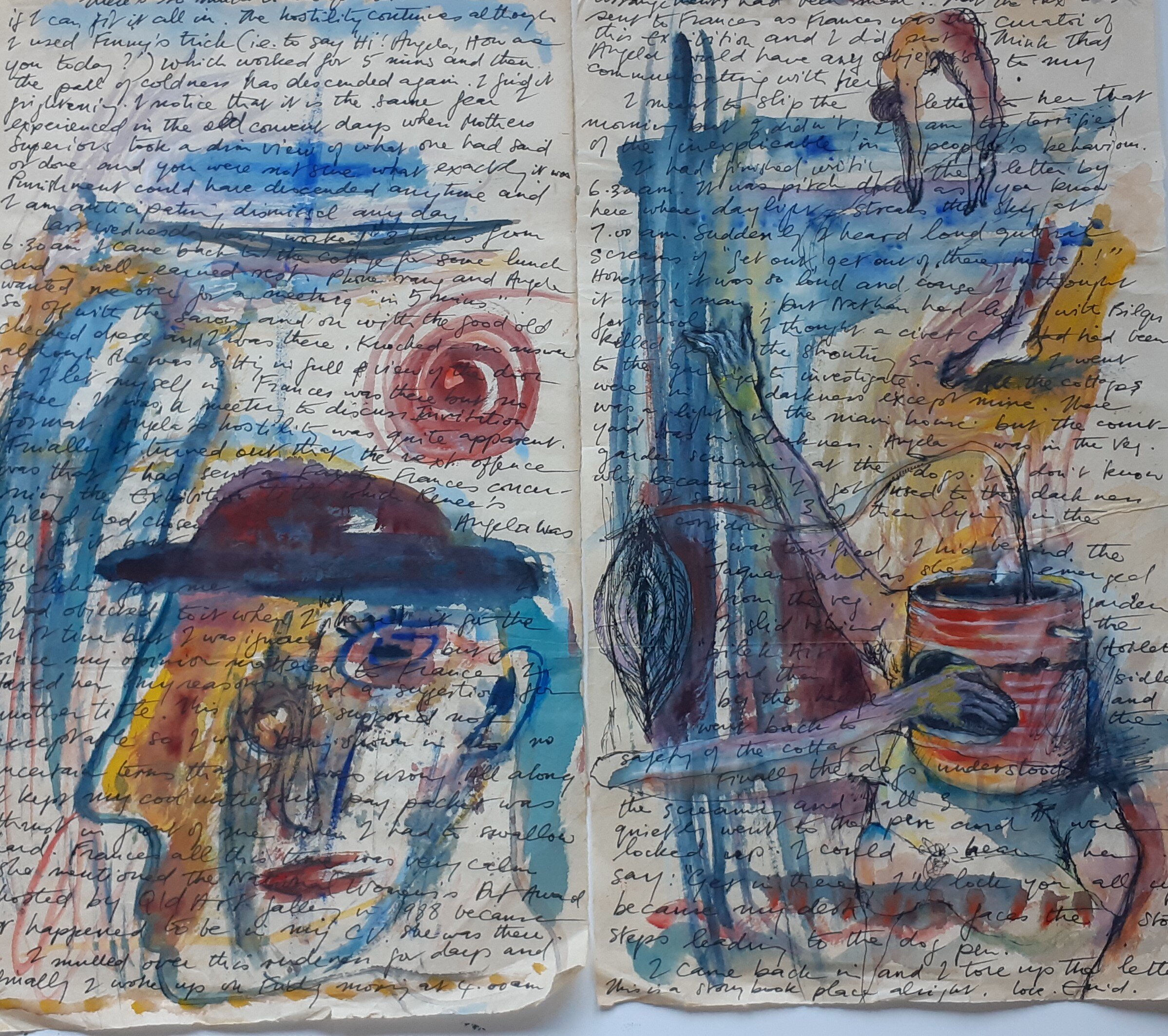

Throughout that Residency I kept a close diary. These blogs are from that diary. I loved the cottage. It was close to an old rambutan orchard, dark and brooding. Only now do I appreciate the strength and inspiration I derived from the flora and fauna surrounding this cottage and my studio; the lotus flowers and their dried centres; fallen fruit decaying into profound blackness; dried and skeleton leaves. These, and the events, both ordinary and extraordinary which took place at Rimbun Dahan were the esoterica which became my points of contemplation; the motifs which were the catalysts to my paintings; the elements which transformed loneliness into solitude, silence into strength, and fear into meditation. The sum total of prayer. Nature became the ballast I needed to keep me grounded through physical and metaphorical storms and blackouts.

So, without mincing words, I will say that on learning of her death, all the memories of deprivation, isolation, unfairnesses and fear returned, and I wish I could go back on that time when I worked alone in what was meant to be a joint- Artists Residency, and do things differently, or tear it all to bits like a piece of waste paper.

Art in a Time of Madness

/The line is drawn

The Rimbun Dahan Residency was politicised and racialised from the very beginning.

On the first morning of my arrival Renee and I sit together outside the cottage having tea. It’s my first day. The air is fresh and warm with a clean smell after the rain, a true Malaysian kampong morning, roosters crowing and the noise of birds and animals around, and the sun picking up heat by the minute. The grassy lawn just beyond the small concrete drain, meant to channel excess water to the bigger drains in the rainy season, is lush green against the dark orchard.

Renee whips out a cigarette. She did that the night before. I didn’t expect it. She smoked while she ate and later as we sat in the lounge room after dinner regardless of my discomfort. To have said anything about this smoking would be to start on a negative note. My discomfort may have seeped into her consciousness as most people’s internal states tend to do. Not everything needs to be said. I never bargained for this, I thought, but I applied for this residency and I must find a way around this or put up with it until the appropriate time when, having got to know each other better, I might say something about the health benefits for both of us of not smoking indoors. That time never came. I didn’t realise until in retrospect, it became clear that this was a ploy.

And then she threw her bombshell: I only mix with Caucasians, she said. My mind spun. Was she blind? Did she possess a mirror? I a dark-skinned person was facing a dark-skinned Eurasian woman who saw herself as white on account of her Dutch surname, Kraal. Almost in the same breath, she said, I hate this place. We’re an afterthought. They had this space and they stuck us here. That unhappy note did not correspond to the excitement she expressed in her letters to me before I came. Looking back at those letters, I realised that she had expected to occupy the Guest House where all the orang putih were housed. This cottage, adjacent to the Indian Driver’s cottage, was a reminder of the colour of her skin. Her bitterness explained the filthy state of that cottage, reeking of cigarette smoke and cat excrement.

That day, the line was drawn. That day the gap between us was so widened as to prevent all prospects of our ever, becoming friends. That day something died within me.

III

Colourism.

Malaysians associate light skin with beauty, a greater potential for achievement and superiority. A skin tone one shade lighter or darker than someone else’s determines where you will stand on the social ladder for the rest of your life. It requires a certain degree of sophistication to bypass pigmentation; to have the grace to go beyond the incidentals of appearance and to look for value in character and personality. That grace is non-existent in Malaysia.

There, there is no ‘brown paper bag test’ as there is in America where a person —especially a woman’s— social standing and career prospects are determined by how much lighter or darker she is than a brown paper bag. In Malaysia, judgement by the tonal scale exists from the time you are born. It begins in families.

The first question which forms in the minds of the most unsophisticated and least educated of Malaysians, is not whether a new born is perfectly formed or healthy and beautiful but, ‘Fair or dark?’ It is even acceptable in families for a mother to point out the dark-skinned child in the family and, insensitively, associate her darkness with a future of low achievement and limited opportunity. This is not racism; this is colourism, and this colourism is prevalent in Eurasian families or families where one parent is Eurasian. It is where disunity in families begins. And this disunity creeps into society. Malaysians are quick to discredit their own especially in the face of Westerners. They are unsupportive of each other.

Colourism is the beginning of low self-esteem especially in girls. The early awareness of being unloved: you are not loved for who you are; you are not loved because you exist; you are not valued for what you are, because you do not fit into the world’s expectations of who you ought to be. This is the internalised racism which is global. This is ironic in a country where the majority of the people you meet are dark. This obsession with skin colour and shades of darkness shows how early in our lives, identities are formed. The Structural Racism we see in the world is simply a perpetuation of the policies and practices of colourism.

Racism in Malaysia has been going on unchecked for decades. Whiteness is valued around the world but nowhere more so than in Malaysia where three different races each with more than three different shades of skin colour, existed side by side for centuries. Malaysians were not unaware of these differences; but they were more accepting of each other’s differences in earlier times than they are today.

In my import —the Catholic system— every Bishop and cleric down to the very last nun who stepped off the boat from France and Ireland to teach, was White. These are the people who dictated right from wrong to us. Is it any wonder Malaysians associate whiteness with perfection?

As if this religious aberration was not enough, the British descended on us and in WW II, through their inadequacy and arrogance opened the doors to that epitome of racist minds —the Japanese— allowing them free reign over us. That over, the Brits came back and compensated for their World War II silliness by carting Malaysian youths to England and Australia to educate them; whereupon the majority returned with a white spouse and a new generation of white supremacists sprung up. It looks as if wherever you turn in Malaysia today there is a white woman married to a Malaysian in high places. Any Australian check-out chick or Czechoslovakian peasant could end up a Puan Sri or a Datin or a Tungku. These are the titled women to whom Malaysians give unquestioning allegiance today, beginning again the cycle of whiteness and the shades of whiteness to darkness-equals-value-equals-superiority. The Serani, who can look anything from a Chinese to a Malay to an Indian, sees herself/himself as Caucasian: : hence, Renee’s I only mix with Caucasians.

To blend in with that superior white cloud whose company she so valued, Renee avoided the sunlight. It kept her skin light. She slept during the day until darkness fell. Then, fully made up, she walked over to the studio in the dark to work. Consideration of skin colour preceded and replaced health concerns. Something was bound to go wrong —and not only with a Vitamin ‘D’ deficiency and its consequences for a woman’s physical and mental health.

Diary Entry (DE) 30/6/95. Renee speaks of healing. She’s a vegetarian. She talks to plants. She’s a heavy smoker…Pollution…She sleeps all day. The Victorians had a proverb on sleep: Six hours for a man, seven for a woman, eight for a fool. Saadi of Shiraz the Sufi mystic was no less unkind: ‘When a man’s sleep is better than his waking— It is better that he should die.’

I wake when she enters the cottage in the early hours of the morning. I lie awake for a few hours. I rise at 6 am. The sky is always dark at that time... I sit outside the cottage to look at the morning star. A diamond solitaire in the black sky progressively turning Saxe blue. The trees in the old orchard are silhouetted against the swiftly brightening sky…Gate of Heaven…Morning Star…Health of the sick…Comforter of the afflicted. The fresh air is comforting.

DE. 1/07/95: Cloud formation at 7 am over the old orchard; grey with silver lining. The sound of cars and motorbikes all heading south towards Sungei Buloh and KL. (I cannot see them. I am deep in this orchard. It is like a protecting womb; I hear them). Workmen, going to work. I love the quiet of the kampong morning. The light comes on suddenly. There is no long twilight here. I love the light between the trees; the sudden shafts of light through dense leaves...Sometimes, patches of light come through between the trees and the darkness makes them sharper, more intense. I love this place.

In ’95, the Rimbun Dahan Artists Residency was still unplanned. The idea was to bring Artists from Australia and Malaysia to work together. The real idea was to show the West the family’s wealth. The cringe still existed. Hence, there were no regulations put in place to create a reasonably comfortable place for both artists to live and work in close proximity. Heavy smoking was, even in ’95, socially unacceptable globally. Renee smoked even in the Administrators’ dining room, their lounge room, the gallery and the studios. They said nothing. She was the Malaysian artist. There were political reasons for their silence.

IV

Concerning the Political

I said in my first blog that this Residency was…politicised from the beginning… In July I met the entire family of the Millionaire, M, who had given us that Residency. We were invited to dinner at their mansion. Renee, Kevin, the artist from New Zealand, Jason an architect from Manchester and I. The family was warm and gracious. Their lifestyle, elegant and simple, the food delicious. For a man of international standing, I found M to be accessible, no airs and graces.

The surrounding landscape had already become inspirational and I had made several sketches of the leaves and lotus centres, the flora, fresh and dry. I couldn’t wait to get into the studio and begin painting. And despite everything that happened later, my admiration for M and my love for that place created by his wife Alice* has remained.

After-dinner there was coffee in the new underground gallery. That’s when the interrogation started. Alice asked, point blank, if my sister had married the Belgian after her husband, a Muslim, had long died. I had no idea. I had been estranged from my large and largely disunited family for nearly forty years: eighteen years in the convent and the last twenty in Australia. I had come to Malaysia, naively thinking that I could to work as an artist with Renee who had invited me to apply for this Residency. But of course, this is Malaysia and you will always be connected to your family. Then, Alice said that my nephew, Rehman, a famous Malaysian author, had snubbed her at his book launch. She never forgot it. Hell-fury ensued. M said that Rehman had been un-cooperative and churlish about a project of his. Perhaps, they expected me to apologise for my family’s misdemeanours. I didn’t even know when I applied for this Residency that they knew my family. Apologising on behalf of someone else was not my style. I would hate anyone to apologise on my behalf. That she was still smarting from the snubbing episode rendered Alice’s intentions questionable; but any speculation on that matter would be inappropriate here.

I loved both my sister and Rehman; but I have always disapproved of their conduct and distanced myself from them. In my opinion, Rehman was arrogant and disrespectful of women, especially strong women. To me, loving people and approving of their behaviour are mutually exclusive: you can love a person and still disapprove of her/his behaviour.

I sat alone in my black silk dress as if on stage, fielding Alice’s questions regarding my family’s private affairs, in front of strangers. The seating arrangements in the gallery assumed a subconscious strategy: M sat to my right; Renee and Alice sat close together on my left. The two girls, M’s daughters, Kevin and Jason sat somewhere beyond, listening in silence. I never expected this indiscretion.

At the end of the night, Renee and I walked across the moon-drenched courtyard in silence to the Artists’ cottage. I knew of Renee’s off and on friendship with my sister and with Rehman. She was still at that time very close to Rehman, but she said nothing in his defence, nor did she try to diffuse the situation in any way. This was the first but not the last time Renee would throw me to the lions. The moon, bright and full, illuminated not just the courtyard but also what might have been the true purpose of my selection to this Residency: that perhaps I was brought here, not only because of my achievements and qualifications, but because there was a backlog of grievances against my family of which I had been unaware but for which I was going to pay.

(Diary Entry) 11/07/95 I must be careful of Renee. She and Alice have grudges. They want me to take sides in their quarrels. I am here to paint, to produce a body of work and that is what I am going to do. Nothing that happens here will go out of here. I will not enter into other people’s quarrels. I will not say a word to anyone in my family about the Residency or what happened tonight. Quarrels are unproductive, and we are creative people. And so, I will not enter into any discussion with M and Alice or Renee about my family.

As it turned out, I was lucky to have been ignorant of my sister’s affairs. I could have caused disaster if I had ventured the wrong information. Marriage to a non-Muslim (the Belgian) would have jeopardised a person’s position with the Syariah court in this Islamic country. A non-Muslim cannot own land in Malaysia. Alice later said in passing that she envied my sister. The land she was on was on a hill; wild, exotic, bound by a river source and dam on one side and surrounded by forest. Was it possible that someone could, in conscience, calculate to deprive another of her home and property? The simple-minded nature of these revelations only reflected the inherent corruption behind such intentions. I am reminded of the Gina/Rose Hancock affair: the relentless pursuit, the uncontrolled hate-attacks, the bullying; the continuous bashing until one woman wears another down and is none the happier for it. I hoped this would all end there and that I would be left alone to work in peace from then on, not jeopardised by family.

I never referred to that night in the Gallery until now. My sister met me later and said that I was not to speak to M or Alice about her. I didn’t need to ask for reasons. I knew why. The probing ended. But not quite. The indiscretions continued, revealing another political scenario.

Renee and I were the second duo of artists to take up the Rimbun Dahan Residency. Renee had told me that the Malaysian Artist, of the first two artists before us, had been troublesome. According to the servants, he had been treated with scant respect —in fact, downright rudeness. I met him later and he confirmed this. You don’t have to ask for information in Malaysia, it comes to you on a platter.

That night Alice told us that the two artists before us did not get on, so she had titled their Exhibition: Mind the Gap in jest. I found this information disconcerting. Would we too be talked about when our backs were turned? I resolved that no one was going to ridicule us. We were going to be respected as Professional Artists. There would be no disagreements for public consumption; if there were disagreements, we would settle them between us.

Unfortunately, despite no serious disagreements, Renee became more and more agitated and stayed away from the studios, claiming in tears that she couldn’t work at Rimbun Dahan because I was constantly peering over her shoulder. As there was nothing to see but an empty studio, that was a joke. I requested Alice for meetings in which we could all talk together in a civilised manner, find out what could be done and address the problems if there were any. She turned down my requests for a meeting and aborted every positive suggestion for the strangest reasons which I will come to later.

I came to the conclusion that some people prefer conflict to peace. It is the kind of disorder that gives them the excitement of seeing someone get hurt; because in every conflict, someone gets hurt. It is the kind of disorder lodged in the hearts of those who derive pleasure from witnessing cock-fights and boxing matches. But this being a public Residency, Alice had to do everything in her power to rectify the mistakes which had been made with the treatment of the Malaysian artist the year before: it was political.

Stories will be told in paintings

Of love for an ancient place

And the things that happened there

steeped in unlove

Blackened branches

Of rambutan trees

Soaked in tears of rain

And wind and storm

Fall, and falling, fell

In the darkest hour of the night

One heavy thud to the ground

Before daybreak.

* Not her real name

V

Fin

Fin picks up my diary and reads: …The VQ stormed out again. Left her cat for a week. I have to feed him. Milo-san. He hates me…sicked-up all over the kitchen floor… shits in the flower pots she brought into the cottage with some cordyline… she talks to plants…she thinks they answer with music…. The cottage stinks of cat-piss and cigarette smoke.

Ew! Fin says, Say something. Tell them. VQ. What’s VQ?

Virgin Queen, I say. Throughout my diary I refer to Renee as VQ

Virgin? Fin asks. Which one? Our Lady of Fatima? Our Lady of Lourdes? She looks at me. Oh, that one? She says. She laughs loudly. What about M--o, K-t, David, Allan, Hashim, Hassan, Nabil, Kupusamy, Leng…She rattles off names real and fictitious. One or two are names of gay men. And…, not to mention the odd orang putih who drops in —in more ways than one. She looks at me directly. Enid, Renee’s a Sixties Malaysian artist, OK? And, for your information —since you’ve been locked away for so long, hooded up and stuck in that convent and then in that down-under place— they’re a clique who buy each other’s work and jump into each other’s beds. Ok? She sweeps her hand in the air miming the jump into bed. Virgin? She sneers.

Shh, keep your voice down. She asked me here. I owe this to her. And you shouldn’t read other people’s diary. I take the diary from her.

So? You going to be grateful for the rest of your life? Gratefulness puts you on your knees.

I know, but it’s more difficult than you think. I’m afraid of the consequences. I can’t stand fights. Wasted energy.

Diary Entry 6/7/95: I just wish Fin would stay away. She’s loud. Familiar with the servants in easy, loose Malay which they pretend to find amusing. She’ll say anything. But she’s all I’ve got. I don’t have transport. I don’t have a telephone; I don’t know my way around. Renee takes the car…and Fin is leaving for the US soon…

*

I am washing the kitchen floor of cat-sick, sweeping the water towards the back door of the cottage with the penyapu lidi when Renee walks in after a week’s absence. She has her hair pulled back severely from her forehead and controlled at the back with a banana clip. She has been taxiing her German friend all over Kuala Lumpur in the residency car. She looks happy.

Just in time, I sing out, I hand her the broom. Your turn, I say, taking advantage of her cheerfulness. But I should have been sensitive to her fragility. She has been through a bad relationship break-up and her father has died. The elderly Chinese lady next door to her place broke Milo-san’s legs a year ago, through spite. So, I stop trying to be funny. Milo-san has been sick, I say.

She stops short, throws the half-smoked cigarette onto the food and hairball sludge on the floor. Look, she says, it’s not that difficult since you are already washing the floor. I look at her in consternation. Her lower lip quivers and pushes up her upper lip, her mouth forms a L’Oreal 216 Red Hot, upside-down ‘U’. I can’t face this, she says. She turns and leaves the cottage. From the half-open blue glass pane of the kitchen window I see her stamping her feet as she walks up the two steps which lead to the dog kennels and the garages and then to the courtyard leading to the main house. Each stamping step the disappointed sulk of a fifty-one-year-old child.

To think I took care of her cat and she didn’t even thank me. I finish the clean-up and try not to be angry. An empty tin of cat food lies near the dustbin. I tear off the label, threw out the tin and created a collage with the two Whiskas images from the paper label. One becomes a black mask and another an image I titled Cat Queen.

Further down the track I will see a repeat of today’s performance which will be far more severe and have more serious consequences for me.

Diary Entry (7/7/95: I never seem to have answers to anything: Only images, useless images. I’ve upset the VQ. I’ll need to get provisions. Will have to walk the Kuang road to the Simpang.

The Kuang Road meets the Kuala Selangor Road at the Simpang. It’s a nightmare of a road. Narrow. Poorly maintained. A dirt track, haphazardly topped with bitumen and subsequently upgraded to simulate a main road going from Kuang to Kuala Selangor. Chunks of bitumen break away from the sides after heavy rain. I have to jump off the soft edges when a lorry or the village bus swerves to avoid oncoming traffic, tilting and threatening to topple. There are accidents on this road. On my way I find fragments of plastic number plates from motor cycles which have been hit at Lorong Atap. I take the pieces back to the studio. I’ve brought a roller and some ink with me and I make prints on joss paper of the numbers on the fragments.

*

First Day. The day I arrived at Subang International Airport, the Residency car was supposed to meet me, but only Fin is there. That’s what big sisters are like. They remember your dithering, even forty years from childhood. I have a bad reputation for losing my way. Fin knows. She wants to drive me to her place first and send me to Rimbun Dahan later. She’s a great cook and I want to go with her. But as we talk, I see Renee emerging from behind a pillar. She comes forward, finger on her lip like a shy child. Renee, I say, I didn’t see you there. She approaches smiling, wordless. Fin steps back behind her, puts her index fingers to her temples like two pistols and mouths the words, Spaced out, man! Then she waves and says I leave you to it, then. She leaves, and my heart sinks a little.

Renee drives me back to Rimbun Dahan in a semi-rundown beige Volkswagen. My dream car, she says, a chuckle in her voice. I’m so excited. A high squeak on the ‘ci’ syllable, like a child with a new toy at Christmas. I’m surprised at this ‘dream car’. As long as a vehicle can take me from A to B, as long as I keep it clean and serviced, it’s a vehicle; not a dream. Alice gave it to me, she says. Alice is the Administrator of the Residency. These people must be rolling in money, to give away a car and a ten-thousand-ringgit Residency to each of us. The long driveway into the grounds of their mansion confirms my calculations. This car must be a gift to her.

I will discover very soon that this is the Residency car which we are supposed to share. But how do you prise a toy from the clutches of a child without inflicting pain? That deception —although I doubt it was deliberate: Renee had simply made herself believe the car was hers — concerned me.

Flashback, 1963: A convent school in Perak. I was a young teacher of twenty-three preparing students for the Cambridge Overseas School Certificate exams. A seventeen-year-old appeared one day in my Fifth Form Art class. Her drawings were artworks, not the works of a schoolgirl. But the Nature Drawing Paper required closely observed botanical renderings. I sat her beside the best girl in class. At the next Art Class Renee told me in confidence that she suffered from claustrophobia. I had a small inkling that this girl was the patient, psychiatrist and couch all in one. As I was ‘the only person who understood’ her, I felt obliged to allow her to leave the class for a bit. The Headmistress, having referred to the master timetable, sent for me. The new girl had been seen wandering during class hours, and would I, and the two other teachers who were there before me, explain why we had allowed this to happen? All three of us, ‘her only confidants’, had been sympathetic to the claustrophobia story. Renee didn’t stay long in that school.

I kept two small drawings of bones she made during that Fifth Form year for many years. They were drawings done in perfect proportion with an artistic flair I found engaging. The work of a true artist. [I returned them to her in 1996 when the Residency was over]

Revelations. After dinner on the first night of my arrival, Renee asks if I’m on HRT. No. Why not? She gives me a run-down on the benefits of HRT for women: younger looks, brighter skin. I could do with some help from HRT. Insolence. But this is Malaysia, get used to it again. It’s where people play fast and loose with the whole idea of discretion. Why beat about the bush? Just be direct, lah. I know about HRT. A big thing that year in Australia too. And I know of its pitfalls.

I ask what she’s working on. Too soon to tell. I deduce from that answer —'artists block’. She has not been working consistently— I know she is into batik, but she thinks she might paint. Painting is not new to either of us. All artists are versatile.

She tells me she has just been through a difficult relationship, recently broken up. I know. She wrote to me about it. What a swine he was, ‘slippery’, ‘not to be trusted’. His vices surpass those of her chief enemy, who happens to be one of my sisters who, she believes, is ‘damaged’, ‘binges’, ‘has mood swings’ and ‘is in need of healing’.

I refrain from judgement or advice. This gut-spill of confusion and anger needs no advice, just a listening ear. Only a naive mind spiralling into the vortex of an impossible oneiric underworld would give credence to everything she’s saying. Let her speak. In retrospect, I should have shown some sympathy. But jetlagged and wishing to go to bed, I said nothing.

Renee lights another cigarette. I shift uncomfortably to the edge of the armchair in which I am sitting. It feels damp. Malaysia’s seventy percent humidity, I think. And yet the room is comfortable enough. She takes a drag and then points to the armchair and says, Milo-san is afraid of the cats in this place. He can’t go outside so he does his business on the armchairs. Stunned, wordless stare from me. She is amused at how knowing her cat is. Hers is the only armchair in which he never pisses. The stain on my skirt is yellow. I wish she had warned me.

I want to start studio work. I am hungry for solitude and for work. Our studios are adjacent to each other and as she is the host artist, it would be presumptuous of me to have gone into the studios and set up for work before she was prepared. I waited. She went home to KKB for days and I had nothing much to do, so I gathered whatever I could find from around the place and made drawings. I found a fruit I had never seen before outside the main gate. Only in the kampongs can one find exotic fruits, mushrooms and orchids. The fruit was yellow to mustard in colour and about 10cm in diameter and 6cm high. I didn’t know what it was. I asked the Malay servants about it. They told me it was an Assam; used in Chinese funeral rites. Later I thought of including it in one of my paintings.

*

Following the cat-sick clean-up incident that day, Renee went across the courtyard to the main house. She returned to the cottage looking distraught, as if she had been crying a lot. She locked the cat in her room and left for her home in KKB. He scratched and cried all night until she returned the following evening. I had by that time become adept at escaping another dose of mumbo-jumbo concerning healing. I would come across the courtyard from the studio and look out for the car. When I see it in the garage, I go for a long walk to avoid her. But this time, I see the car and go straight to the cottage and I confront her. That was cruel, Renee, I say. You shouldn’t have locked him up. He cried all night and I couldn’t feed him.

I thought that’s what you wanted; she said.

VI

The Price of Avoidance

At the end of 1994, I received a letter from Renee. She had fond memories of me, she said, as her Art teacher and the only person who understood her. I hardly knew her. Sentimentality aside, her letters urged me to apply for a Residency in Malaysia. I had never heard of it. There would be a shared cottage, individual studios and a car at our disposal, and all expenses paid. A phantom was opening the doors of the dark room where I resided with disappointing political and personal migrant experiences. This Residency seemed too good to be true. Her letters described the place in euphoric terms confirming its reality. The doors creaked open wider to admit the fresh air and sunlight of a new dawn. I saw this invitation as a godsend and applied for the Residency, recklessly breaking two self-imposed rules: Rule One, never have an Exhibition or agree to work with an ex-student on her or his request. There is always a catch. If you do well, you’ll be accused of crushing a tender flower; if you do poorly, you’ll be seen as a loser. Two, be sceptical of sentimentality. It goes hand in hand with cruelty. But, too eager for the sights, smells and sounds of home, I ignored the alarm bells even when they became louder with Renee’s subsequent letters. In these letters, she hinted of possible conflicts, outlining strategies for taking cover ‘in the event of our not getting on’. This was not a joke. A damper fell on my enthusiasm. Nine months of Art and discovery; of working with Renee and meeting with Malaysian artists; of collusion in valuable ideas and of perhaps making a contribution to the family for its generosity to artists, all took a back seat to the fear of conflict. But my application had been accepted and I had taken leave of my job. It was too late to pull out. As I was confident that I would be able to overcome any obstacles maturely, I never thought of unfairness. And what I saw from afar as small stumbling blocks, in close-up were insurmountable phantom mountains.

*

I arrived in late June. By August, Renee, citing intimidation, came to an agreement with Alice that she work at her home in Kuala Kubu Baru, KKB, virtually making a farce of that joint Residency. Alice agreed to Renee’s whims. She had to. Her track record with the Malaysian artist the year before was not edifying, to put it mildly. Renee was the Malaysian artist this year. Like rodents in a bush waiting to pounce, the Malaysian public had its eyes on her, or so she thought.

From time to time, Renee made token appearances by returning to the cottage. On these rare occasions, if she was not asleep in her room, she sat on the veranda smoking. I sat with her occasionally and listened to her monotonous sermons in judgement of her enemies delivered between drags on her cigarette. In the absence of grace, every setback becomes self-referential. One creates negatives where negatives never existed and uses them like a razor-wire fence in self-protection against the world; picking up every word and turning it against oneself. Renee was inarticulate except in complaints.

Her friends dropped by to let me know how sensitive she was; advised me how to show compassion and with each advice I became less sympathetic and more dispassionate. One day Rehman, the writer, my nephew, rang me to say Renee needed a little manja. She was, in his words ‘A manja girl.’ Maybe I should have been less cool; exposed her machinations. But I couldn’t bring myself to descend to uncivil conduct. And a fifty-year-old needed no manja, no mollycoddling.

There are two great evils in the world, said Cecil Beaton: boredom and being a bore and the latter is the worse of the two. I should have understood Renee’s anguish and commiserated. But she was such a bore. If you told her a joke, she repeated the punch line in a flat tone of voice and killed it.. As I listened to her one day, a drizzle fell in a slanting fall against the banana grove a few metres from where we were sitting. Where the raindrops caught the evening light like running stitches in white thread, I was reminded of a Hiroshige print Rain at Shono (1833). I used this image in my next painting Hujan Liris. (It was sold at the James Harvey Gallery here in Sydney after the Residency.) Sensing my boredom, Renee stubbed out her cigarette in her saucer with such force, the saucer danced about screaming against the glass-topped table like an insect which had just been stabbed. She went into the kitchen. and I followed her later. She lit another cigarette. You intimidate me, she said, shoving cat food into the fridge uncovered. You are aggressive. I was shocked but not silent this time. In what way? I asked. How could I be aggressive and intimidate you when you are not here? You are never here, Renee, I said as calmly as I could. I sensed that she was spoiling for a fight.

Your paintings…she gestured —too big —aggressive. You are abnormal. You work too much. Maybe you are anxious about the exhibition. The put-down didn’t escape me. My CV was impressive. I had done many painting exhibitions and had recently been selected for the 21st Alice Prize Exhibition for a very large triptych. I was enjoying that uninterrupted time to paint. My prints were small; my paintings large. I needed that spacial experience, and this Residency was giving it to me. Renee turned around from the fridge and exhaled smoke in my face. I pulled back at that rudeness. How crude, I thought. She waved her hand in front of my face to clear the air, impressing on me that it was not accidental, it was deliberate. That’s when I realised that she was disturbed. Nevertheless, I was stung. Renee wanted to be in the Guest House, not in this cottage, and she preferred to goad me into some kind of confrontation, so that she could move out without being blamed for it. The innocent party, she was always the innocent party.

I loved what I was doing; absorbing the landscape and weaving it into my paintings; wallowing in my freedom to be solitary; enjoying that uninterrupted time to think and to work. These reasons had to be kept away from her present state of artists block like salt from an open wound. Negative thoughts, poor diet and lack of exercise can work havoc in one’s mind; cause a blockage; the parameters which staunch creative fluidity and disallow new Artistic conversations. Many things disturbed her, my studio practice for one, and whatever disturbs someone causes inexplicable reactions, elicits insolence and unfair remarks. These encounters with her made me want to leave the Residency but they paled into insignificance in the face of my love for the place and for my work.. For the first time I had the experience of an uninterrupted flow of work. I wrote letters home and told of my inability to sleep as I moved from one panel to the next in the triptych which had become a trademark as it were. Triptych based on the Gothic concept of the number three; this religious aspect of the significance of the number coupled with my intimate and internalised knowledge of the number three which characterised my date of birth: 13/3/39. So many threes. Divide 39 by three and one gets the number 13. I have worked in the threes for a very long time.

I wanted to leave, but what to, after giving up my job? I couldn’t. I had fallen in love with the place. I should have said something to someone, but there was no one to turn to. In the years away from family and home, I had become self-reliant; forgotten how to solicit sympathy; how to complain; how to ingratiate myself with other women, and so, I bore her disrespect and insults rather than cause trouble, and like Proust’s Swann in the face of Odette’s lies, my soul bore them along, cast them aside, cradled them like dead bodies…and was poisoned by them. It disturbed my work. I had to avoid her.

I took long walks and stayed in the studio writing and painting until she left the cottage. Tired and hungry from walking and working one evening as I waited for the car to leave so that I could be alone in the cottage, I headed there to have my dinner and a rest. Renee had cleaned out the entire fridge and pantry. It was too late and too far to walk the Kuang Road alone to the Simpang to get some food. I went to bed hungry.

Surprisingly, she appeared the next day in the studio. I made no mention of the empty fridge. With a calm face, like a mask —the large red mouth, the hair pulled back from the brown forehead and the eyebrows completely plucked, replaced by single drawn lines— she said, I thought you were here just to paint, so I cleaned out the fridge for you yesterday.

*

Fast forward to October 1995. Ian was visiting. Alice suggested that we take a holiday. She even offered us the use of the Rimbun Dahan van. We took a road trip to Penang. Light Street convent, the chapel, the smell of the sea and memories of childhood holidays were consoling until our return. Entering the cottage, I saw the bookshelf empty of all Renee’s books except for the recently published monograph on Brett Whitely which I had given her. The kitchen had been cleared of every utensil. The fridge empty. There was not even a knife. It was surreal. Sinister. There were bits and pieces of paper and spilt food on the kitchen floor. The phantom of a thief hovered around. A large Nescafe bottle with some rice in it was in the pantry, nothing else. I opened it to discover broken rice, with grit, chaff and mouse droppings, like the third quality rice we had to have in the War when the Japanese took all the first quality white rice. Where did this come from? I had not seen it before. You would have to use a tapis to separate the chaff from the grain and dirt. It was horrible.

Despite the lateness of the hour and fatigue, we drove out to Sungei Buloh in search of dinner. I was too upset to eat. No one had said a word about Renee’s departure. The next day, Ian went to return the van keys to Alice. Rather than ask about our holiday, Alice asked him how I was. Did she want to relish the news that I was hurt? Ian said I was in shock. Things had gone missing. Alice seemed surprised. She suggested we re-equip the cottage kitchen and the Residency would reimburse us. We shopped the next day, shortly before Ian left for Australia. I wanted to leave with him but it was too late and I needed to get over this and to go the distance. I am not a quitter. Heavy-hearted for days, I became worse when the workers told me that in our absence, Alice and Renee spent a day removing all Renee’s belongings from the cottage.

Civility, the hallmark of a moral code from which all goodness radiates, had died in Malaysia. I grit my teeth and continued alone. I was in the pincer grip of insanity and its ally. I had to stay grounded, or float, like a figure in a Chagall painting. Both women later declared themselves feminists. That they found pleasure in injustice and victimisation of a woman alone, makes them other than feminists, just people knotted up inside with self-loathing.

There was a tallboy left in Renee’s bedroom. I opened the drawers. A fine dust of black soot remained in the corners of each drawer. The stale cigarette smell lingering in the room was sickening. I feared for her lungs as much as I feared for her soul.

VII

The Residency is extended

October 1995. Shortly before Renee moved out. Renee had been away in Kuala Kubu Baru (KKB) for the week. I woke with my heart pounding in unfounded fear when someone entered the cottage at 2.30am. I knew it was her. She had the keys., so I couldn’t process my discomfort. and the sensation that I didn’t know what exactly I was afraid of. Maybe it was conflict. There had been so much continuing conflict in my family that I ended up trying too hard to please, as if in being a people pleaser, you could make the arguments go away. After an intermittent sleep that morning, I woke again at 6.30am. Our rooms adjoined the kitchen and I was afraid to wake her before midday which was her rising time. I went to the studio without breakfast. There were tea making facilities there.

From the walkway of the main house, concrete slopes plunged into two fish ponds between the M’s mansion and my studio. Sitting outside my studio on the edge of the fish ponds in the morning and watching the cascade of water booming open by an underground mechanism and plunging into the fish ponds down the concrete slopes, was a peaceful yet exhilarating sensation. The fish, some of them rather large, frolicked in energetic leaps. M’s genius as an architect combined with Alice’s talent as a landscape artist made what might have been a wilderness, an amazing oasis. I watched as Alice stood on the walkway, hands on hips, looking into the distance. I thought of Jane Austen, painting with her words on a wide canvas. Alice was painting that wide landscape with her mind’s eye. Very soon some changes would occur and a tree or some element in that landscape would be shifted and positioned as a jeweller would set precious stones to their best advantage in a bracelet. This was an evolving landscape, balanced by control where verdant lawns met and melded into the browns and emeralds of the wilderness.

It was a pity, in retrospect, that this place should have been torn apart by heavy-hearted byways of negatives. I wish there was something I could have done at that time to alleviate Renee’s unhappiness. She was needy. Needing approval as much as she believed she was in need of healing. The remedy lay at her doorstep: exercise, healthy eating; the appreciation of nature and art. Instead, she drove several times to healing classes, commuting between KKB, Kuang and Kuala Lumpur (KL). She wanted me to join her. I couldn’t. I didn’t believe in Crystal clutching. To me, sleeping through the fresh beauty of a morning is like living in regions of long Nordic winters; courting sadness and depression. I refused to believe in Vitamins and Supplements. I knew where her unhappiness was coming from, but I seemed powerless to help, and I blamed myself for the large canvases I chose to work on —as much a desire to enter and be absorbed by technique and landscape as they were an attempt at resolving the darkening situation that was enveloping us. I desperately wanted to be immersed in all that surrounding beauty, and desperately wanted to escape.

I returned to the cottage earlier than usual that afternoon to rest and found Alice and Renee in quiet conversation on the patio, two glasses and a jug of lime juice between them. Meetings like this usually took place in the M’s dining room which was right opposite my studio, so perhaps they had come to the cottage for privacy. I had been asking Alice for the three of us to meet, if only to talk to each other in a friendly manner over a cup of coffee.

Renee had told me with some delight about an exhibition with a French artist: Renee who found it difficult to meet deadlines was a few hours late to set up their exhibition, so the Frenchwoman began to set hers up. She was ready to leave when Renee arrived with a friend. When they saw the Frenchwoman’s work in situ, Renee was distressed. Her friend went up to the woman and, pointing to each of her installed works said, What is this? You, you, you. What about poor Renee? The Frenchwoman took all her works down and the Gallery division began. That eventuality was disturbing when I thought about my very large canvases. So, I kept asking Alice for a meeting to clarify, dates, times and space allocation in a civilised manner, before the exhibition. The meeting, was finally secured. for the 19 January 1996 and this was the scenario:.

We met in the dining room. Alice was busy walking about locking and unlocking the glass doors between the dining room and the kitchen. She was obviously ignoring me. It’s so hard to talk to someone who will not look at you. You feel invisible, and an invisible person cannot have a voice. ‘ Alice,’ I said, ‘Could we have a meeting sometime with Renee to talk about the exhibition?’

Alice: I don’t see the point in it. Relationships being so strained as they are. She refuses to sit down. She keeps locking and unlocking the glass doors. I feel a hollowness in my chest where there would have been a feeling of patient acceptance if I had been dealing with a child..

Me: It would be good, just to talk to each other

A: I’m telling you there’s no point in a meeting. You are not speaking to Renee. So there! It’s too late. Why ask for a meeting now. You don’t believe this Residency is working. To quote you, ‘things are not going well.’ She was misquoting me. Workmen had dumped some stuff on one of Renee’s paintings in the storeroom. I didn’t want Renee to think that I had been neglectful. The store room was adjacent to my studio. I had told Alice that ‘things were not going too well as it was, and I didn’t want Renee to think I allowed them to do that. I didn’t tell Alice that I had called Renee to tell her and she had hung up on me. I wanted to keep conflict out of the picture.

Me: Alice, we must separate the personal from the professional. I’m asking for a meeting so we can discuss space, invitations, interviews etc.

A: We’re thinking of separating you. One in The Star, one in The Straits Times.

I suspected she was going to create another ‘Mind the Gap’ story. Me: Why are we being separated? The public doesn’t need to know Renee has left.’ I was determined to stall that kind of petty story: ‘Oo these two artists couldn’t get on so we are separating them etc.’ Spectator sport; blood sport.

She was still fiddling with the glass doors. I sighed. Am I dealing with primary school kids here? I’ve never been a Primary school teacher. Alice: The Straits Times will not touch whatever was in the other papers. And you are adults, so don’t expect me to be sniffing around your quarrels.

I really didn’t know how she arrived at that illogical conclusion. The crudity of sniffing like a dog; comparing herself to a dog was revolting. I hated it when she mentioned ‘quarrels’. It sounded degrading. ‘All this is so childish.’ I said. ‘I mean, nobody even told me that Renee was leaving the cottage. It was upsetting.’

It was such a strain talking to a moving person who wouldn’t look at me. Something would happen later on and I would finally say something to one of the well-known artists I knew and she would mouth the very words I was now thinking: Alice is terrified of you. She doesn’t think the way you do. She doesn’t think straight. She never thought she would meet with an intelligent Malaysian woman. Further down the track, something would happen to one of the children on the property. A sadistic teacher beat his palms with a ruler so that he couldn’t hold a spoon or eat his dinner. When his mother told me that, I said that I didn’t belong there and couldn’t intervene. I wish I could confront that teacher. I suggested she approach Alice with the problem. She would have had more clout than I. She looked away, saying, ‘Kadang kadang, dia tak fikir berberapa baik.’ And I understood. There are times when she doesn’t think straight.

To my remark that Renee had left without anyone saying anything to me, Alice said,: I assumed you knew. Renee was devastated by it all, she added.

Me: By what? She shrugged. She didn’t know. Since I arrived,’ I said, I’ve had no means of communication or transport because Renee had the car and refused a phone because she had a phone at home in KKB. I have a family at home in Australia.

A: Well if things were so difficult why didn’t you say so earlier and go!

Me: Artists don’t take up a Residency and leave because of problems which can be fixed…

A: Well it’s too late now. You should have said something earlier and gone...

Me: That would be unprofessional. If I take on a project, I take it to the bitter end.

A: Turning back to the glass doors, shouts, If the end is bitter, then quit NOW. We don’t want bitter people around. You’ve got the car now, you’ve got the telephone, what more do you want?

‘What more do you want’. I couldn’t understand why she was saying this. She repeated it every time she had an opportunity. It took years after the Residency was over for me to realise the import of these words

Me: I’ve got them now, but for the first 4 months of this 9-month Residency I had no car. For the first 7 months I had no telephone. And this is a remote place. I have a husband and son at home and I need to be in touch and to have some privacy. My brother-in-law suicided and my sister rang and you said it was a private phone and you didn’t relay the message to me. I didn’t get in touch with my family until a week after the funeral, and they are just in Petaling Jaya.

I bit back my hurt. Renee knew my family. She knew what happened, she knew I had no phone and she never got in touch. Her personal misgivings overrode compassion. When and why do women become this way?

A: I’m sorry about that. I cannot be held responsible for other people’s problems. We’ve all had our problems this year.

She had had a death/ suicide? in her family as well.

Me: Perhaps Renee should have thought about me when she refused the phone line and when she equipped the cottage with her belongings. Artists come from afar and they cannot be expected to furnish a kitchen in the live-in quarters provided. If Ian had not been here, what would I have done?

A: Don’t blame Renee, M doesn’t want you to have a phone. She had forgotten that I was there when M insisted that I have the hand phone from the van and she had argued against it. The entire interview unnerved me. The fact that she didn’t sit down to talk. She seemed to be shouting, thrashing about as if under a spell.

*

Back to Alice and Renee drinking lime juice on the patio. They didn’t offer me a drink, but I sat down. This was my chance to be with the two of them. I asked if we could agree to have the exhibition earlier, say at the end of February as I wanted to be home for Andrew’s first day at University in March. Alice turned to Renee and asked what she thought. It was clear who was the boss here. Renee took a drag on her cigarette and whispered; I am not prepared. The conversation ended there. The residency was extended by another month to become a ten-month Residency. I went to my room and shed a few tears.

VIII

Of Giving and Taking

Renee had said that Ian and our son Andrew were welcome to visit and stay for a while with me if I chose to take up the Residency. Andrew arrived in October, thin and strained. I had been away from home for four months and although I loved the place, I regretted having taken up Renee’s invitation. I tried to keep everything that was happening with Renee from him. I cooked dinner on the night of his arrival and set the table on the patio with flowers and candles and got him to go to the studio and invite Renee to dine with us. She was sitting by the pool in the dark with a candle and her sketchbook. He returned from that mission looking as if he had climbed out of the burning pit nearby. We had dinner together, just the two of us in silence.

I had been alone for months, and a CD player /radio would have been some solace in the intense blackouts which were common in Kuang, and which remained unattended to for days. In these blackouts I could do nothing but sit alone in the dark. The darkness was so intense that if I lit a candle, the flame illuminated a small circle just below it and I couldn’t read. Andrew brought me a radio. As well, he got to work on the ruined Residency radio which one of the previous artists had left in the rain. Now we had two radios. I was listening to O mio bambino caro---in my studio when I heard Renee on the staircase. I called out to her and suggested we could have one radio in the cottage and one in the studio. I hadn’t seen her for days. I gave her a hug.

I can see, she said, that I will have to get used to your mood swings. Damper number one. She had told me about my ‘mood swings’ This too was something I worked out later. Renee had been a close friend of my sister Rosna, a compulsive and incessant talker. She once drove me from Klang to Rimbun Dahan and never stopped talking all the way. It’s impossible to describe how exhausting travelling with a compulsive talker is. You become the captive audience they need

Instead of going down to her studio, she turned and went upstairs. There was a door at the foot of the stairs which separated the studios from the staircase. I followed her. Please stop sulking, Renee, I said, Andrew is here. She slammed the door in my face. I went back to my studio and my upper arms felt weak with hurt. I decided to confront her. I followed her to the cottage and just as I was entering the back door, she grabbed her bunch of keys and was getting ready to leave. It was a Saturday. Andrew had gone to KL. The trains and buses were not co-ordinated as they were in Sydney and I had no means of contacting him. If she left, he would have been stranded at Kuang station.

In retrospect, I should not have worried. The people in that village were kind and friendly. They were accustomed to strangers who came to Rimbun Dahan. Andrew would have been cared for, and perhaps, even taken home to dinner at someone’s place and brought back to Rimbun Dahan on the back of a motor scooter. That’s the way true Malaysians are. When my friend Barbara came from Sydney to be with me later, she was stranded at Sungei Buloh station one evening. She arrived back late at Rimbun Dahan with a carload of teenagers who were absolutely delighted to have made her acquaintance and to drive her there. There was nothing to worry about but I was too tense to have made sense of anything.

Me: Before you take the car Renee, Andrew is in town and I will have to meet him at Kuang station. Can you wait a little?

R: I need to be in KKB before dark.

Me: There’s still a lot of time and the car…When I mentioned the car, she wrenched the keys from the bunch of her personal keys and flung them on the bar fridge,

R: Take the car, she shouted.

I had encroached on her dream; tried to wrench the one thing she loved from her hands. Why had Alice not clarified things? The keys slid off the fridge top and fell onto the sideboard near me. I was standing between the sideboard and the back door. The daughter of one of the servants, coming home from school, hearing the shout, peered through the kitchen window at us. This girl was the abridgement of pre-pubescent interfering inquisitiveness, continuously peering into any open window. I knew that her next move would be to come in by the back door for the excitement of a fight. I held on to the door knob to prevent it.

R: Yelling. How dare you sh..sh..stop me from going out. She could hardly say the words. Her face became black with rage. I could see the white froth at the corners of her mouth. I should have let her leave, but I put my finger to my lips and pointed to the face at the window. The girl left the window and was off, presumably with tales to tell.

Me. Trying to keep my cool. My heart racing; my hands trembling. I’m not trying to stop you. I just want us to talk. Have you given people the impression that I was a bully, intimidating you? I asked

R: I didn’t say those words! I don’t want to talk about it.

Me: You don’t have to shout. It was hard to prevent myself from trembling, but I had to say what I needed to say. We need to talk. She began to twist and turn, writhing like a bird trying to extricate its tied foot. I said as calmly as I could; my heart beating fast: I have been left here alone in blackouts night after night and you come in the next day to say what a good time you had at dinner with your friends in KL the night before.

R: You have your sisters.

Me: Yes, miles away up in Ulu Langat and Petaling Jaya. I didn’t come here to work with them. And, what are these notes you leave around whenever you come and go?

I found notes stuck to the fridge. One said: ‘In power over others is energy begot. Aloof people create interrogators…Poor me, aloof, INTIMIDATORS!!’ Alice in one of her snarling, defensive moments which corresponded with Renee’s weeping, flapping, flailing performances, had said that I was the cause of Renee’s leaving the Residency; that I had intimidated her by peering over her shoulder to look at her work. That was a joke. Her studio was empty. She was working at home. Perhaps, verbally challenged as they both were, what they meant but couldn’t articulate was that she had felt intimidated by my studio practice which was different from that of the salon painters of her circle. And as for energy, perhaps some people derive energy, not from investigative and energetic artworks, but from fights, directly or by proxy.

Me: Look, Renee, I’m sorry if I have upset you, but what I want to say is that these people might be millionaires but they have given us this Residency and we need to make it work. You cannot take so much and give so little in return. M has given us a lot. All he wants to see is that his artists are working peacefully and…

She turned around, and went out by the front door, stamping her feet and weeping audibly as if she had learned to cry from some method acting class. In that state of distress, she went to Alice to complain, and the smear campaign against me began.

What I had forgotten in my forty years away, was that in Malaysia, it is inappropriate —for a woman especially— to ask a direct question as I did. That was to be garang, confrontational. I should have found a shoulder to cry on. That person would then settle my opponent. I had no friends there and no memory of having resorted to these niceties.

What I didn’t know about Renee was to come.

That night I left a note for her which said something about her anger; about taking a lot and giving very little in return. When my sister heard of what I had done she said,

‘You fool, you played into her hands. She has taken words out of context from private letters, done a cut and paste and photocopied and distributed them. I knew it. I knew it. I knew she was going to make mince-meat out of you.’

But I had judged her by myself. That was something I would never have done.

IX

The Prisoner and The Friend

I was ten when my best friend since our first day in Primary School, disappeared. Her family had moved on. I cried myself to sleep; kept thinking of the fine crease in her forearm and her creamy skin and her loveliness and didn’t want to go back to the Convent Bukit Mertajam Primary School. I cried myself to sleep for about a week; and then, only the occasional thought of the fine crease in her forearms and her creamy skin remained, and I forgot her. When I was twenty-seven, and a nun, at the Convent Bukit Nanas, I was called down to the parlour one day, and there she was, elegant, twenty-seven and lovelier than ever with her perfectly beautiful newborn son in his bassinet. He was to become an Australian and International artist whose untimely death of a heart attack in 2009, shocked and grieved us all.

*

After Renee’s theatrics with keys and tears, Alice’s etiquette took a plunge and sank way below unacceptable levels. Her mascara-outlined blue eyes looked fierce with frightening frowns. Her words slurred in a sludge of guttural-nasal commands as one would have heard in an outback pub or ejected from the mouth of a truck driver or workman on a building site. She watched my every move. from an invisible panopticon across the courtyard.

Shortly before the Residency Exhibition, Ramli Ibrahim, the dancer called. He came in a beautiful blue car and parked in the driveway. Everything about him was close to perfection, from the way he carried himself to his every accoutrement. He came into the cottage and remarked on how well kept it was, and how I, like the rest of my family was house proud. I had found a genuine ikat fabric rolled up and thrown under the billiards table in one of the studios, dusted it off and hung it on the wall in the sitting room. I used the subtle cobalt blue tints within its design against the russet hues in my painting, Hujan Liris, light rain. I rubbed red earth from the burning pit near my studio into the weave of the canvas and with a mixture of oil paint and linseed, painted it over in Venetian red to create the russet hues as in the fabric. Ramli leaned against the kitchen bench, folded his arms and asked about Renee. I was more interested in the gracefulness of his movements than in talking about Renee. I thought of the Sufi Mystic Haykali’s poem: Thou art there.

The movement in response to another movement —thou art there

The grace of the graceful, not the mind of the graceful —thou art there…

I said she was finding life in the cottage difficult and didn’t say more. She had left by then.

We went to my studio. There had been a storm and one of my paintings had flown across the doorway. Ramli lifted the large canvas with one arm and shifted it easily. He is the master of the Odissi, the Indian classical dance and very fit. We went down to the Gallery and Alice came down to join us. I left her to talk to Ramli alone and went back to the cottage. All that had happened so far had diminished me and I was uncomfortable in her presence. Before he left, Ramli expressed his admiration of Alice who —only that morning, unnerved me by sneering: You’re only putting on a brave face…why don’t you go— I accepted what Ramli said without comment.

The next morning, Alice stopped me on my way to my studio and asked: Why did Ramli come? Did you ring him or did he ring you?

Me: He rang and asked to visit. He knows my family from way back. I walked away regally; as regally as any prisoner can pretend to be.

Alice appointed Frances Cummings, an accomplished Queensland Arts Administrator as Organiser and Director of our Exhibition. I was afraid when I saw her. A white woman. Was I going to become the meat in another sandwich? She turned out to be a blessing. Calm and totally impartial. With her around, I felt safe. We talked from time to time and she asked to visit. I bought a pair of traditional metal, hand-forged Chinese scissors at the Simpang for Mal, her husband who had seen a pair I had, and liked it; the type of scissors my mother used in the War. I said they had to pay me a token ten cents for it because my mother deemed it bad luck to give anyone sharp instruments, they signalled break-ups. Frances had been one of the Organisers of the National Women’s Art Award Exhibition in Queensland for which I had been considered. Mal was related to the well-known artist Elizabeth Cummings whose work I admired, so we had much to talk about. As soon as Frances and her husband left, Alice sent for me. The interrogation which I so resented began: Why did you send for Frances?

Me: I didn’t, she asked to visit me and Mal came as well.

A: Did you say anything to prejudice her against Renee? I looked at her the way one looks at a well-groomed white poodle who had taken to rolling himself in the mud.

Me: I don’t need to do things like that. I do NOT do things like that.

A: It’s important not to do that.

Me: Well I DON’T! OK?

Members of my family dropped in occasionally, unannounced, and I was subjected to more interrogation. Who called whom? It seemed she was on the lookout for Rehman and one day my sister visited with her youngest son who was also tall. She went berserk. Was it Rehman’s Pajero she saw parked in the driveway? She walked about in the vegetable garden near the cottage. All she needed to do was to come over to the cottage and say hello. Just as all she and M needed to do, was to call the Residency quits, something which, day after day, I hoped would happen. I had tried my best, by my silence, not to perpetrate ill feelings and pettiness; to make that Residency work. I never complained. I found solace in the landscape and every painting of mine was connected in some way to the flora, fauna and events which took place at Rimbun Dahan, from the launch of the Restu Festival to the performance of the Jazz Club. And yet, nine years later, the journalist Kamina Lyall was paid to lie. She wrote: